The Black Paintings

Using the al secco painting technique, Goya used oils to paint directly onto the plaster walls of his home, called La Quinta del Sordo, making the 15 paintings (only 14 survive*) that have come to be known as a single group called The Black Paintings. He created the images between 1820 and 1824 (some claim 1819-1823), when he would have been 74 years old.

"Goya's growing political, intellectual, and human isolation may well have led him to decide to paint for no one but himself. The Black Paintings... are in effect the most extreme manifestation of the growing misunderstanding and estrangement between modern society and the artist. It is true that many subsequent artists painted or drew or carved works of art that they intended to be enjoyed and understood by only themselves. But never before and never since, as far as we know, has a major, ambitious cycle of paintings been painted with the intention of keeping the pictures an entirely private affair. The very fact that Goya had recourse to fresco painting instead of the more usual canvas and oil is proof enough that he never expected his paintings to be displayed in public, and since very few people made their way out to visit Goya's retreat, these paintings are as close to being hermetically private as any that have ever been produced in the history of Western art."

Goya by Fred Licht , Page 204. Abbeville Press Publishers, 2001

"The most celebrated pictures of Goya's last years are the series of 14 so-called "Black Paintings" done for a suite of rooms in the coutry house just outside Madrid that he purchased in 1819. Aged 74 when he began this group, he had already been dangerously ill in 1819, as the Self-Portrait with Doctor Arreita, a gift of gratitude to his doctor, records. Old age and infirmity have been suggested as a linking theme for this series. But the overall meaning has never been satisfactorily explained. All the pictures were painted directly onto the wall and they are all, to a greater or lesser degree, damaged. In 1878 they were transferred to canvas supports. Goya painted these works very rapidly, using broad strokes applied with large brush, palette knife and possibly sponges. He may have regarded them primarily as a technical experiment. Attempts to tease out connections with the earlier Caprichos or Disastros have proved difficult. They are perhaps best considered as hermetic self-contained fantasies, despite several elements being based upon, or strongly evocative of, earlier images. Suggestions that they contain an essentially nihilistic message are not convincing. If any connection can be made to earlier work it is with the "Proverbios," or "Disparates," a short series of 22 prints made by Goya between 1816 and 1823 but unpublished until 1864."

Frank Milner, Goya, page 23 – 24, Published by Bison Books, UK, 1995.

Goya's the "Black Paintings"

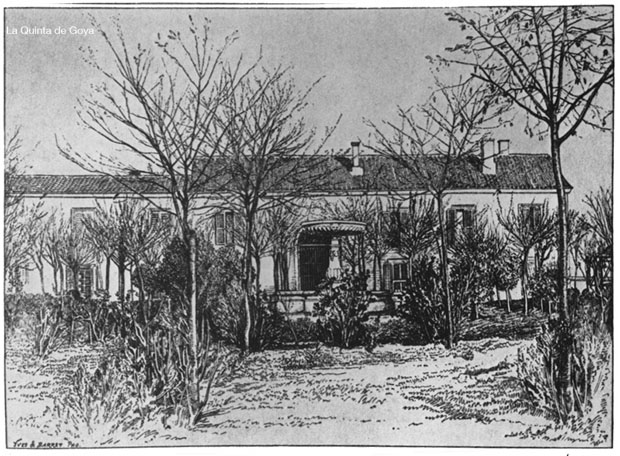

La Quinta de Goya – Goya's home in Spain and location where he made the Black Paintings

Writings about the Black Paintings

De Salas on the Black Paintings

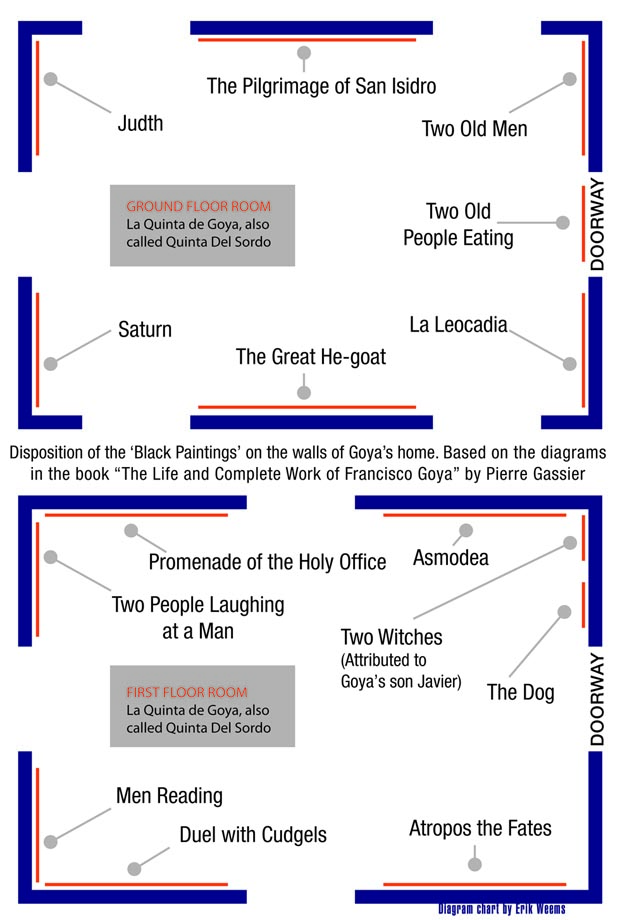

La Quinta de Goya - House in which Goya painted onto the walls the 'Black Paintings'. The structure on the left is the original building and the right represents the expansion. The building was demolished in 1909. Click image to enlarge

The House of the Black Paintings

Goya purchased the Quinta del Sordo (aka La Quinta de Goya) on February 27, 1819*. The name Quinta del Sordo refers not to Goya, who was deaf by this time, but to the previous owner, who was also deaf, a situation that has created some confusion over the centuries in art history.

Goya's new property was about 175 Kilometers (107 Miles) to the south of Madrid, the land consisting of approximetely ten hectares of farmed ground and a small house. La Quinta de Goya was near Manzanares, and had extensive views of that city.

After purchase, Goya had the house enlarged and in the addition he decorated the two floors (using what is called the al secco technique), one below serving as a reception room, and the one above as a dining area. The plain whitewashed walls were the surfaces used for painting the oil images which in time left them susciptible to decay due to the unstable grounding of the wall surface.

The Paintings

These two groups of paintings which Goya created are often given as one of the reasons Goya went into exile five years later, the images being understood as dangerous to have so prominently displayed on one's walls with the unpredictable King Ferdinand VII (Fernando VII) in power. On the other hand, the images remained, uncovered, in the house until removed approx. 1867, which contradicts the theory the paintings themselves were a danger to anyone associated with them.

Completed after his serious illness of 1820, the paintings are sometimes described as random images, but the inventory by Goya's friend Antonio Brugada after Goya's death includes seven small preparatory sketches which indicate Goya had a single cohesive plan for the cycle of paintings.

The mysterious meaning of the images and the centuries of art history hagiography has made the specific interpretation difficult. The physical relationship of one painting to another along with philosophical and symbolic references may be a guide to their meaning.

Often the images are seen as linked to his relationship with Leocadia Weiss, a young attractive woman who was living with him. She had been hired as a housekeeper and was accompanied by her young daughter Rosario (aka Rosarito). Later, when Goya moved to Bordeaux and then Paris, both Leocadia and Rosario came to join him.

The paintings are typically described as Goya's growing consciousness of his old age, the expression of his inevitable mortality coupled with a general disillusionment with life and people.

Does this explain the nightmare aspects of these paintings?

One of the main descriptions given of the Black Paintings ("pinturas negras de Goya") is actually in error: they are in various shades and tones and are not meant to be so 'black.' Degradation from time and because of the restoration work (mostly performed by Salvador Martínez Cubells between 1874 to 1878 when the images were transferred onto canvas mounting) has modified the images from what Goya originally put onto the walls at Quinta del Sordo.

For example, the Duel with Cudgels (Duel a garrotazos) is sometimes described as a combat between two figures buried up to their knees in a blackened bog while surrounded by an agricultural scene. Investigation into contemporary photographs and the layers of the painting at the Museo del Prado show that the original image probably had the figures fighting in a field of high grass. This would reduce the psychological imagery of a scene of violence in a bog (or quicksand) to one in which violence is occurring in a coherent farming scene.

The naming of the Black Paintings

The titles are based upon what was given to them by his family and utilized in Brugada’s inventory. Description of the pictures were made by French writer Charles Yriarte** in his early Goya biography of 1867. Yriarte's titles are in agreement with the titles still in use by Goya's descendents in 1867.

On the ground floor by the main door was a likely his-and-her portrait of the master and mistress of the house, with la Leacadia (aka Una Manola) on the left, and on the right Two Old Men (Dos viejos or Un viejo y un fraile) which may be a self-portrait by Goya in which he depicts himself as an elderly, white-bearded man with a demonic figure talking into his deaf ears (as noted by art scholars, the round-shaped mouth in Goya's art often indicates a demon figure's communication). Goya depicted himself in a similar fashion in one of his later Bordeaux drawings entitled 'I am still learning.'

The matching la Leocadio painting in the collection of the Museo del Prado shows the female figure leaning against a mound with a low railing, which is typically understood to be a depiction of a mourning Leocadia Weiss in a graveyard setting. According to x-ray investigation, the image likely had an earlier arrangement of the female figure leaning against a hearth and dressed without the mourning clothes.

"What is certain is that on the walls opposite the door into the room, on each side of the window, we again encounter the two protagonists, hidden behind the cloak of their symbolic representation: Leocadia appears as Judith, an obvious allusion to the latter’s victory over Holofernes by virtue of beauty and treachery, while Goya appears as Saturn eating one of his children.

The writer Xavier de Salas speculates on some of the meanings that could be found in how the paintings are grouped, expressions of melancholy in the theme, and speaks on an assertion made by some that a more explicit imagery was painted over within the Saturn painting.

Next to Leocadia, on the main wall, was a portrayal of The Witches’ Sabbath, in which the Devil appears as a horned goat, surrounded by his female disciples, all of them hags, except for the enigmatic figure of a young woman, almost a child, who bears no relation to the bestial conclave in which she finds herself. The significance of this figure in the composition, however, remains a mystery.

On the opposite side of the room was the Pilgrimage of St. Isidore, in which groups of people and couples wander through an arid landscape in the far distance, while in the foreground a group of young figures are singing at the top of their voices. If one compares this scene with that of the Meadow of St. Isidore, painted in 1788, the extent of Goya's profound spiritual transformation becomes immediately apparent. The latter exudes all the joie de vivre of a spring evening, with the buildings of Madrid bathed in a pink and white light in the distance, and the majos and majas picnicking and chatting on the grass. In Quinta del Sordo, in the painting that both inventories describe as Pilgrimage of St. Isidore, the countryside is scorched and the men wander aimlessly through it. The joie de vivre has become melancholy, with an element of violent anguish in the expressions of the frenzied singers in the foreground.

The meaning of one of the Black Paintings, Two Old Men Eating, is made clear by the writer's observation that the door positioned near the painting served as the entrance and exit to the kitchen.

Between la Leocadia and the counterpart portrait of Goya, above the door, was the painting of Two Old Men Eating, probably an illusion to the door’s function: it may well have been the one through which dishes from the kitchen were brought in.In order to visualize the appearance of either room, we must bear in mind what Yriarte wrote, and also what the paintings themselves tell us. The rooms were of ‘very modest dimensions’, which would have made the figures in the paintings seem larger: certainly larger than they now appear in the museum in which they are housed. This would also have made them appear even more overpowering. It should be remembered, too, that, according to the inventories, the furniture was upholstered in yellow, which would have further emphasized the gloominess of the paintings, as would the matching yellow curtains that in all probability framed the doors and windows.

In the case of the first floor room, we have not been able to establish such clear links between the different compositions, but undoubtedly the overall theme was that of death, and, as has already been said, the significance of each painting would have been enhanced by its physical relationship to others in the group. To the left of the door was Atropos or The Fates, a picture that still remains an enigma: there are, as is well known, only three Fates, but what, then, is the identity of the fourth figure, whose wrists appear to be bound? The next scene, on the other side of the door or window, was the one called The Strangers or Cowherds in the inventories, which is commonly known as The Fight with Cudgels. It shows two men fighting with cudgels, locked in mortal combat and imprisoned up to their knees in mud or sand. In painting this composition, Goya was recalling Saavedro Fajardo’s 75th allegory or 'emblem', Bellum colligrit qui discordias seminat, which, according to the author’s interpretation, means: 'Medea sows [in order to prepare for the theft of the Golden Fleece ] ... / ... the teeth of serpents ... and squadrons of armed men spring forth, who, fighting amongst each other, are destroyed...'. The engraving of the scene shows a fight between men who seem to be buried up to their waists or half submerged in water. Saavedra went on to clarify his allegory by explaining how some Princes stir up discord, and thereby find themselves faced by wars and unrest within their countries. By fermenting disharmony, they think they will be able to enjoy peace and quiet, but things turn out quite contrary to their designs. At the time that Goya was recalling this allegory, it could well have been applied to the policies of Ferdinand Vll and to Spanish politics in general.

Opposite the wall of the entrance door, on both sides of the door or window, were the compositions of Two Men, as it is called in Brugada’s inventory, or The Politicians, as Yriarte describes it, and Two Women (Brugada) or, alternatively, Two Women laughing their heads off (Yriarte). The latter painting, which shows two women laughing at a man indulging in the vice of Onan, would seem to hold the key to the meaning of both works. The incessant talk of the politicians, one of whom is reading a newspaper that they seem to be passing comment on amongst themselves, was perhaps, in Goya’s eyes, as sterile as the solitary pleasure which the women are making fun of.

On the wall to the right of the entrance.door, which must have been divided by a door or window, were the Pilgrimage to the Fountain of St. Isidore and Asmodea. ‘Asmodea’ is spelled with the feminine ‘a’ ending, rather than as ‘Asmodeus’, the conventional spelling for the evil slayer of husbands, but we do not know the reason for this change of gender; nor do we know why she is shown flying over groups of warring soldiers or what significance there is in the mountain that dominates the scene in the background. In the case of the Pilgrimage (also known as the Holy Office), however, with its figures in 17th century dress, we can assume that there is a connection with the steps taken by Ferdinand Vll to revive the inquisition soon after his restoration to the throne. This was an anti-liberal measure, which Goya seems to have classified as anachronistic by the old-fashioned dress he gave the black-clad man on the right, with his large collar, like the ones worn during the 16th and 17th centuries. There is also an implicit criticism in the grotesque way that he has portrayed the monks in the procession.

Finally, next to the door was the most enigmatic of all the paintings: The Dog, whose significance Yriarte clarified by defining it as A Dog fighting against the Current. Perhaps this is how Goya saw his own situation: as a dog who was barely able to keep his head above the water or the sand, a personification of the proverbial ‘swimming against the current’. We have already stated on several occasions that these murals in La Quinta were conceived in the same spirit as the Proverbs. There are also a number of other, small compositions that were inspired by the same sentiments: the four in Besancon Museum, for example, and other series, of which four are in the museum in Munich and two are in Spanish collections. All of these contain certain elements that link them thematically to some of the lithographs of the same period. As far as portraits from this time are concerned, their scarcity indicates Goya’s growing isolation, since the only ones that he did paint were of his closest friends: men such as Dr. Arrieta, who, as has already been mentioned, appears in a portrait along with the artist himself, and also Ramon Satue and Tiburcio Pe’rez Cuervo, in whose house Rosario Weiss took refuge, and Don Jose’Duaso, in whose home the artist himself sought refuge during the early months of 1824, when he felt that he was in danger of arraignment. As well as these, he did a portrait drawing of Francisco Otin, Duaso’s nephew, and an extremely fine portrait of Maria Martinez de Puga, about whom we know nothing, but in whose portrait, by his sober composition and his brilliant use of black, Goya achieved a monumental quality similar to that of his later Bordeaux portraits."

Excerpted from the book GOYA by Xavier de Salas [Amazon]

Published 1978 by Mayflower Books, New York City.

Copyright © 1978 Arnoldo Mondadori

Bibliography for information on this page:

GOYA by Xavier de Salas [Amazon]

Descontexto (Accessed Sept 2019)

Footnotes:

* A painting referred to as Two Witches is usually attributed to Goya's son Javier Goya.

** As stated in the 1914 Goya biography by Hugh Stokes, Yiarte "...visited the Duke de Montpensier at San Telmo, and the Duke de Osuna at Alameda. The Duke de Alba opened the Palace of the Liria to him, and he was cordially assisted by Frederico de Madrazo, Zarco del Valle, Francisco Zapater, and Valentin Carderera. Many of the Goya family papers were placed at his disposal." - Page IX, from the preface to Francisco Goya; a study of the work and personality of the eighteenth century Spanish painter and satirist, by Hugh Stokes, published 1914 by G. P. Putnam's Sons, London.

GOYA NEWS ARCHIVE

Goya's the "Black Paintings"

La Quinta de Goya – Goya's home in Spain and location where he made the Black Paintings

Writings about the Black Paintings

De Salas on the Black Paintings

AMAZON

Goya The Terrible Sublime - Graphic Novel - (Spanish Edition) - Amazon

"From this headlong seizure of life we should not expect a calm and refined art, nor a reflective one. Yet Goya was more than a Nietzschean egoist riding roughshod over the world to assert his supermanhood. He was receptive to all shades of feeling, and it was his extreme sensitivity as well as his muscular temerity that actuated his assaults on the outrageous society of Spain." From Thomas Craven's essay on Goya from MEN OF ART (1931).

"...Loneliness has its limits, for Goya was not a prophet but a painter. If he had not been a painter his attitude to life would have found expression only in preaching or suicide." From Andre Malroux's essay in SATURN: AN ESSAY ON GOYA (1957).

"Goya is always a great artist, often a frightening one...light and shade play upon atrocious horrors." From Charles Baudelaire's essay on Goya from CURIOSITES ESTRANGERS (1842).

"[An] extraordinary mingling of hatred and compassion, despair and sardonic humour, realism and fantasy." From the foreword by Aldous Huxley to THE COMPLETE ETCHINGS OF GOYA (1962).

"His analysis in paint, chalk and ink of mass disaster and human frailty pointed to someone obsessed with the chaos of existence..." From the book on Goya by Sarah Symmons (1998).

"I cannot forgive you for admiring Goya...I find nothing in the least pleasing about his paintings or his etchings..." From a letter to (spanish) Duchess Colonna from the French writer Prosper Merimee (1869).

GOYA : Los Caprichos - Dover Edition - Amazon